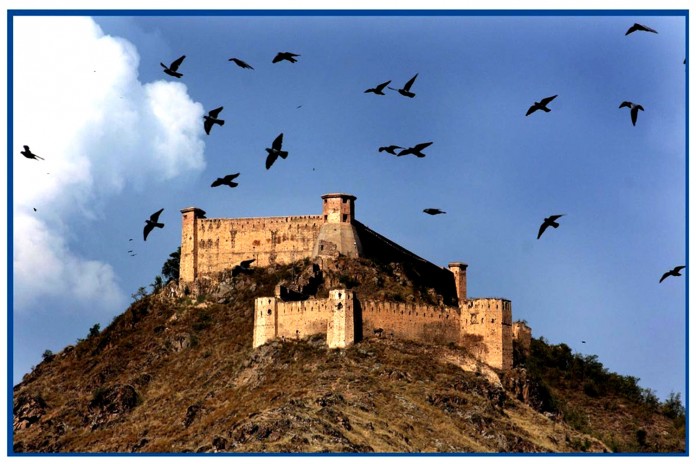

During the first visit, Akbar had directed Sayyid Yusuf Khan Rizavi Mashhadi, his governor, to build the Nagar-nagar, or Naga-nagari as as Suka puts it around the slopes of Hari-parbat or the Kuh-i-Maran (literally, the hill of snakes), and the work was completed at a cost of one crore and ten lakhs. The construction of this great bastioned stone-wall was undertaken, it was given out, chiefly with a view to provide work for the people. Under cover of this construction it was, perhaps, also intended to overawe the people of the valley. Suka says that the Mughuls were to live within the wall so that the soldiers could not, then, molest the local people. The work was supervised by a Kashmiri, Mir Muhammad Husain Kant by name, and completed during the reign of Jahangir. In the Palace there was a little garden with a small building in it in which Akbar, according to Jahangir deputed Mu’tamad Khan to put the garden in order and repair the building. It was “adorned with pictures by master hands” so that it was “the envy of the picture gallery of China”. And Jahangir called the garden Nur-afza.

Palaces were erected and gardens were laid out. These added a charm to the natural beauty of the country. During his second visit to Kashmir in 1592 A.C. = 1000-1001 A.H., Akbar directed operations against Aju Rai, the ruler of Tibet Kalan (major) and Khurd (minor), parts of little Tibet (Baltistan) – who offered resistance. The latter was consequently replaced by ‘Ali Rai who held a principality in that vicinity. Jahangir refers to ‘Ali Muhammad, the son of ‘Ali Rai, deputed by his father to be attached to the Mughul court.

On this second visit, Akbar was accompanied by Bakhshi Nizam-ud-Din Ahmad, the author of the Tabaqat-i-Akbari. Akbar spent the summer of 1597 A.C. in Kashmir, introduced a lighter assessment of revenue and returned to Lahore in the early winter. Towards the close of Akbar’s reign, a severe famine occured in Kashmir. It developed to such an alarming extent that the emperor had to transport grain and cereals from Sialkot to alleviate the misery of the sufferers. Two priests, Father Hierosme Xavier, a grand-nephew of St. Francis Xavier, and Beroist-de-Gois who accompanied Akbar at his request to Kashmir, relate their experience of this famine. The famine, they say was so grievous that “many mothers were rendered destitute and having no means of nourishing their children exposed them for sale in public places of the city. Moved to compassion by this pitiable sight; the father brought many of these little ones, who soon after receiving baptism, yielded up their spirits to their creator. A certain Saracen (Muslim) seeing the charity of the Father towards these children brought him one of his own; but the father gave it back to the mother, together with a certain sum of money for its support; for he was unwilling to baptize it, seeing that, if it survived there was little prospect of its being able to live a Christian life in that country.”

The new land assessment which had followed the remittances of the tax, called baj tamgha, resulted in an increase of revenue, which, as recorded by officials, amounted to over a lakh of Kharwar. A Kharwar was equal to 3 maunds and 8 seers of Akbar’s reign, and was reckoned at 16 dams of Akbar’s currency. In normal times, a maund of rice could be purchased for five annas.

In the reign of Akbar the Subah of Kashmir included Kabul and Qandahar, according to the A’in-i-Akbari.

The re-alignment and construction by Muhammad Qasim Khan, Akbar’s chief engineer, of the great empire route by way of Gujrat, Bhimbar and Shupiyan ensured the regularity of traffic with India.

References:

Sufi,G.M.D (1996). Kashmir Under The Mughals. Kashir: Being A History Of Kashmir(pp.248-251) Delhi:Capital Publishing House.