Review

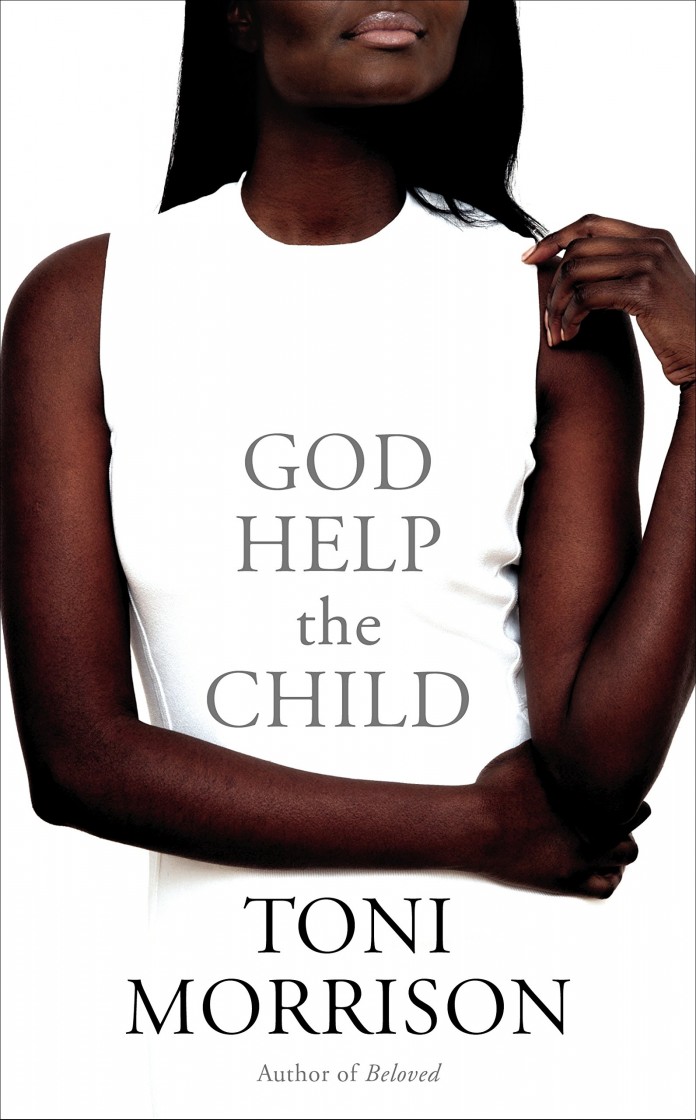

Spare and unsparing, God Help the Child is a searing tale about the way childhood trauma shapes and misshapes the life of the adult. At the center: a woman who calls herself Bride, whose stunning blue-black skin is only one element of her beauty, her boldness and confidence, her success in life; but which caused her light-skinned mother to deny her even the simplest forms of love until she told a lie that ruined the life of an innocent woman, a lie whose reverberations refuse to diminish … Booker, the man Bride loves and loses, whose core of anger was born in the wake of the childhood murder of his beloved brother … Rain, the mysterious white child, who finds in Bride the only person she can talk to about the abuse she’s suffered at the hands of her prostitute mother … and Sweetness, Bride’s mother, who takes a lifetime to understand that “what you do to children matters. And they might never forget.”

As children we have gentle, wordless expectations that the big people in our lives will endeavor to keep us from harm, or, at the very least, not harm us. It’s the sacrosanct social contract: that adults will feed, clothe and protect us, that they will keep our bodies alive long enough for us to devise adult survival strategies of our own.

Child abuse cuts a jagged scar through Toni Morrison’s “God Help the Child,” a brisk modern-day fairy tale with shades of the Brothers Grimm: imaginative cruelties visited on children; a journey into the woods; a handsome, vanished lover; witchy older women and a blunt moral — “What you do to children matters. And they might never forget.”

At the heart of the novel is a woman who calls herself Bride. Young, beautiful, with deep blue-black skin and a career in the cosmetics industry, she was rejected as a child by her light-skinned mother, Sweetness, who’s been poisoned by that strain of color and class anxiety still present in black communities. “It didn’t take more than an hour after they pulled her out from between my legs to realize something was wrong,” Sweetness says. “Really wrong. She was so black she scared me. Midnight black, Sudanese black.”

Bride’s father is also unwilling to accept the child’s dark skin and walks out on the family, accusing Sweetness of infidelity. And so Bride grows up, pinched by hunger and shame, craving love and acceptance. “Distaste was all over her face when I was little and she had to bathe me,” Bride says of her mother. “Rinse me, actually, after a halfhearted rub with a soapy washcloth. I used to pray she would slap my face or spank me just to feel her touch. I made little mistakes deliberately, but she had ways to punish me without touching the skin she hated — bed without supper, lock me in my room.”

But one mistake has devastating consequences. To get her mother’s attention, Bride accuses an innocent woman of a terrible crime. As an adult, Bride sets out to make restitution to this woman but bungles it. She knows only how to turn heads and suppress emotions; she knows nothing (as yet) of kindness and compassion.

Strangely, Bride’s desire to cleanse her conscience angers her lover, Booker, who abruptly abandons her. Bride seeks solace in drugs, drinking and sex, but she’s haunted by Booker — “I spilled my guts to him, told him everything: every fear, every hurt, every accomplishment, however small. While talking to him certain things I had buried came up fresh as though I was seeing them for the first time.” She takes to the road to track him down.

Miles from home, in Northern California logging country, she suffers a car accident and is taken in by a white hippie family. Their self-sufficiency and indifference to money startles her, and, as she recovers in their home for some six weeks, she becomes close to a child in their care named Rain, who was badly abused by her prostitute birth mother and her mother’s johns. In Rain, Bride finds a friend; they understand each other in the easy way of children. The interactions between the two — one stark black, the other “bone white,” one adult, one child, but emotionally the same age — make for the still center of this furious story. For Bride, this episode is transformative and healing; for the reader, it’s all too brief.

There’s an important plot point I don’t want to spoil (especially since the surprises in the book are disappointingly few), but there are ghostly developments throughout: Bride starts losing her body hair and her breasts. Her body becomes smaller and smaller, her period is strangely late. She nurses the “scary suspicion that she was changing back into a little black girl.” Stranger still, this development is only apparent to our protagonist; no one Bride encounters acknowledges her peculiar transformation.

In this shape-shifting form, she eventually finds Booker in another part of the woods, living in a trailer near his eccentric aunt Queen. And we come to understand how violence has shaped Booker’s own life, how his family has been shattered by tragedy.

Toni Morrison has always written for the ear, with a loving attention to the textures and sounds of words. And the natural landscapes in her books have a way of erupting into lively play, giving richness and depth to her themes. Her novel “Tar Baby” (1981) opens with this description of a river: “Evicted from the place where it had lived, and forced into unknown turf, it could not form its pools or waterfalls, and ran every which way. The clouds gathered together, stood still and watched the river scuttle around the forest floor, crash headlong into the haunches of hills with no notion of where it was going, until exhausted, ill and grieving, it slowed to a stop just 20 leagues short of the sea.” The long arms of the story embrace you before you fully understand where you are or what is happening. You read with total trust, because in a place this alive, there’s surely more to come.

In “God Help the Child,” however, we get clipped first-person confessionals and unusually vague landscapes: “The road looks like a kindergarten drawing of light-blue, white or yellow houses with pine-green or beet-red doors sitting smugly on wide lawns. All that is missing is a pancake sun with ray sticks all around it.” The settings feel flat, the tone cynical. There are swirls of brutal personal histories, hurried vignettes and blatantly untrustworthy monologues. (“It’s not my fault,” Sweetness protests. “It’s not my fault. It’s not my fault. It’s not.”) The reader is positioned as a judge over a cast of characters standing accused of the same crime: their inability (or unwillingness) to confront and take responsibility for the suffering of children in their care. Instead, like Sweetness, they choose self-righteousness. Or, like the hippie couple in the forest, they seem unable to face the crimes.

Morrison herself handles child abuse with a cautious disgust, not with the terrifying closeness of her first novel, “The Bluest Eye” (1970), in which an 11-year-old girl is raped by her father. The world of “God Help the Child” is crawling with child molesters and child killers — on playgrounds, in back alleys — but they remain oddly blurry, like dot-matrix snapshots culled from current headlines. When they join the scene, it’s rarely as full citizens of the narrative, and this is a loss. As Booker notes of one predator: “Bald. Normal-looking. Probably an otherwise nice man — they always were. The ‘nicest man in the world,’ the neighbors always said. ‘He wouldn’t hurt a fly.’ Where did that cliché come from? Why not hurt a fly? Did it mean he was too tender to take the life of a disease-carrying insect but could happily ax the life of a child?” The pity is that the book itself never struggles to answer the questions it poses and keeps these men at the margins.

There are many other characters I’d also like to know more about, whose strategies and coping mechanisms and pleasures I wanted to understand, but the novel withholds so much information. I found myself reading between the lines, sucking the marrow out of every sentence. It’s even difficult to pin down when the book takes place: Bride sounds contemporary, but Sweetness’s voice seems to belong to another era entirely. Curiously, the abundance of first-person confessionals does little to invite actual intimacy. They reminded me of reality TV — thin declarations of trauma followed by triumphant dismissals of enduring hurt. It’s too easy for the reader to scratch at the superficial posturing and say, “That person is hiding something.” Yes, pain, but what else?

In the world of “God Help the Child,” there are few caregivers or true friends, no therapists or social workers, and so the adult victims cultivate thin shells of resistance and scrabble to seek justice. I was left with the bitter supposition that childhood is the perfect condition to be manipulated by adult power because it is self-perpetuating. Children become adults and carry with them a trauma imprinted on the body and memory. And there is always the fantasy that a new child means new life: “Immune to evil or illness, protected from kidnap, beatings, rape, racism, insult, hurt, self-loathing, abandonment. Error-free. All goodness.”

With cutting severity, Morrison touches on possibilities of redemption, only to yank them away again and again. “They will blow it,” Queen observes of Bride and Booker. “Each will cling to a sad little story of hurt and sorrow — some long-ago trouble and pain life dumped on their pure and innocent selves. And each one will rewrite that story forever, knowing the plot, guessing the theme, inventing its meaning and dismissing its origin. What waste. She knew from personal experience how hard loving was, how selfish and how easily sundered. Withholding sex or relying on it, ignoring children or devouring them, rerouting true feelings or locking them out. Youth being the excuse for that fortune-cookie love — until it wasn’t, until it became pure adult stupidity.”

But every now and then, “God Help the Child” steps away from moralizing and yields to the slow, tender, dangerous art of storytelling. Morrison brings back her paintbrush and indulges the reader with color and dread as she vividly evokes Booker’s tight-knit family and his idolized older brother: “The last time Booker saw Adam he was skateboarding down the sidewalk in twilight, his yellow T-shirt fluorescent under the Northern Ash trees. It was early September and nothing anywhere had begun to die. Maple leaves behaved as though their green was immortal. Ash trees were still climbing toward a cloudless sky. The sun began turning aggressively alive in the process of setting. Down the sidewalk between hedges and towering trees Adam floated, a spot of gold moving down a shadowy tunnel toward the mouth of a living sun.”

So we are lured by beauty into a scene that ends in evil and horror. The best stories coerce us to live inside terror and instability, in the messiness of human experience. They force us to care deeply for everyone, even the villains. Morrison’s obvious joy in language (especially evident in the passage above) entraps and implicates the reader, and we read ourselves into spaces that would make our better angels shudder.

But too often we get a curt fable instead, one more interested in outrage than possibilities for empathy. Like Sweetness, Morrison doesn’t seem to want to touch Bride either — at least not tenderly. The narrative hovers, averts its eyes and sucks its teeth at the misfortunes of the characters.

And like Bride, I was left hungering for warmth. I wanted to be lured even deeper into that awful golden landscape. I wanted to tug at the sleeve of the storyteller and say, “Yes, yes, I know all that, I get the message, but the story is the thing; tell me the part about the trees again, and don’t forget the sunlight.”

References

Walker, K. (2015) Toni Morrison’s ” God help the child”. New York times. Retrieved on 2nd June, 2016 from

God help the child (na) God help the child a novel. Book browse. Retrieved on 2nd June, 2016 from

https://www.bookbrowse.com/reviews/index.cfm/book_number/3207/god-help-the-child