Where does originality begin? Start by breaking free of the sources of information.

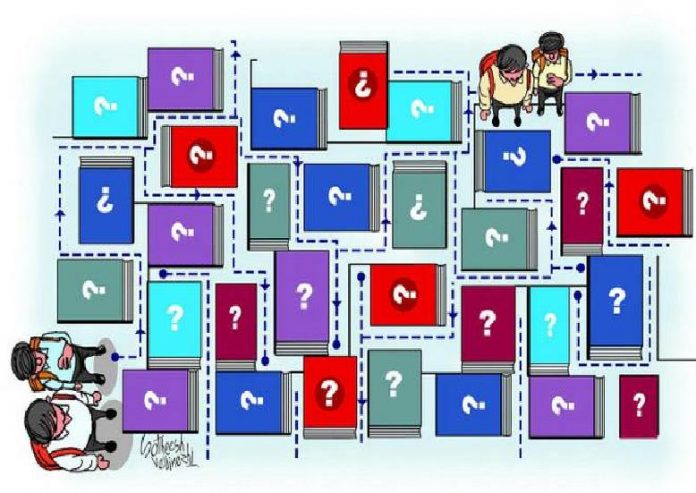

One of the readers of this column wrote in response to last fortnight’s piece, asking how one goes about using old building blocks to create a new structure. Is it possible to actually come up with something original? When so much has been written and said about a topic, what can one say that is new? How do you go about sifting through the material you have read to create something that makes sense, without simply reproducing what others have said?

I’ve tackled this question before, in different ways, but let me see if I can provide another take on it.

SYNTHESIS AND ORIGINALITY

Firstly, the act of synthesis is not necessarily about originality. One can be original in terms of ideas or perspective, and bringing old elements together in a new way can do both. This is why, when ten people paint a sunset, sitting at the same balcony, we could get ten different paintings — even though they all paint from the same view. Each person is viewing that sunset through their own lenses, some with spectacles, others with contact lenses and yet others with neither. Each person is mentally brushing that sunset with their own tints, drawing on their unique way of seeing colour, shape, position and relationship. So we could get one painting where the sun looms large on the horizon, another where the foreground dominates, and yet another that is just an abstract riot of hues. The important thing, in each case, is to produce the sunset that they see — not to simply “reproduce” it.

One way to approach the task is to begin by thinking about the story you want to tell, or are being asked to tell. What is the main point you want to make? What is the essence of the question or task you’ve been assigned? Every collection of facts, however dry, can be put together like a narrative. It could be a definition (what is this?), a process or product (how do you do this and what do you get?), an explanation (why is it this way) or an exploration (what might be the consequences?).

So what you need to do is to figure out this narrative thread and then string your points on it. The theme or the question will give you an idea about what points you need to include and what can be left out.

GOING BEYOND

Some tasks do not call for a very high level of analysis. For instance, most examination questions stop at the level of definition, description or explanation. In these cases, you really don’t need to worry too much about synthesis. Rather, you are only being asked to show that you can recall what has been taught or read. But sometimes you have questions that challenge you to go beyond this, where the examiner wants to see whether you have really thought about the topic and can bring together what you have read in your own way.

Ah. There’s the catch. What is meant by “your own way”? Again, we get tied up in knots around the question of originality. But let’s clarify this a little. Most of the time, examiners (or teachers) are not looking for an absolutely new idea or perspective. All they want is a sense that you have indeed explored the subject and internalised it in a way that you can talk about it without constant reference to the text. Unfortunately, the way most education in our country works, we are encouraged to simply reproduce the text, and if we are able to repeat, word for word, what our book says, we are considered to have “mastered” the subject.

So when we get to a point, maybe in college, where we are asked not to do this, but instead use the text as stimulus and actually free ourselves from it… well, we just don’t know how to deal with it.

WAYS OF THINKING

A few simple pointers might get you started on this way of thinking.

Read the text (or texts) carefully. As you do this, make notes, dividing your page into two columns. In the first, put down key points from the text. When you are doing this, make sure that you put down the page numbers and the specific authors you are referring to (if you are reading several papers related to a topic). In the second, put down your observations, questions, or doubts related to those points. Here you can also connect each individual paper with others, beginning the act of synthesis.

Once you’ve got a sense of the material, put it away — and I mean, shut the book, close the window, put away the papers. Spend some time studying your notes and observations.

Consider the question or the task you’ve been assigned in relation to the text. What does it demand — definition, description of process or product, explanation, exploration? Do you need to combine different ideas about the topic — which is where synthesis comes in?

Go back to your notes and now, construct your answer based on what you have written. Return to the original text only when you need a specific clarification or elaboration.

You’ll find that what you say is truly in your own words, an interpretation and synthesis rather than just a reproduction of the text. You have actually “freed” yourself from dependence on the original author’s words.

And in a very important way, that is where original thought begins.

REFERENCE:

MARCH 13, 2016.Freedom from the text.The Hindu.retrieved from

http://www.thehindu.com/features/education/freedom-from-the-text/article8346119.ece